By sewing garments from recycled and found materials, I am exploring manifestations of femininity within my matriarchal line. I have always been drawn to aesthetics of femininity – soft, floral, light – and I have felt connected to a feminine identity and image; I have also been enthralled with clothing as a means of expression and creativity since I was young. Using sewing and clothing as my medium allows me to both critique and connect with aspects of my feminine identity.

I began my work intending to portray cycles of creation and decay by constructing garments made of foliage. I was drawn to the way that foliage transforms as it dies, and I found this to be a compelling visual as I considered being a young woman trying to conceive of the future in the face of climate change. I was specifically interested in considering this reality through the lens of intersectional ecofeminism, which highlights the dynamics of gender within human domination over nature, manifesting in imperialism, colonialism, animal agriculture, materialism (including in the fashion industry), capitalism, and, ultimately, climate change. Ecofeminism implicates all modes of oppression, recognizing that “all forms of oppression are… inextricably linked (Gaard 24).

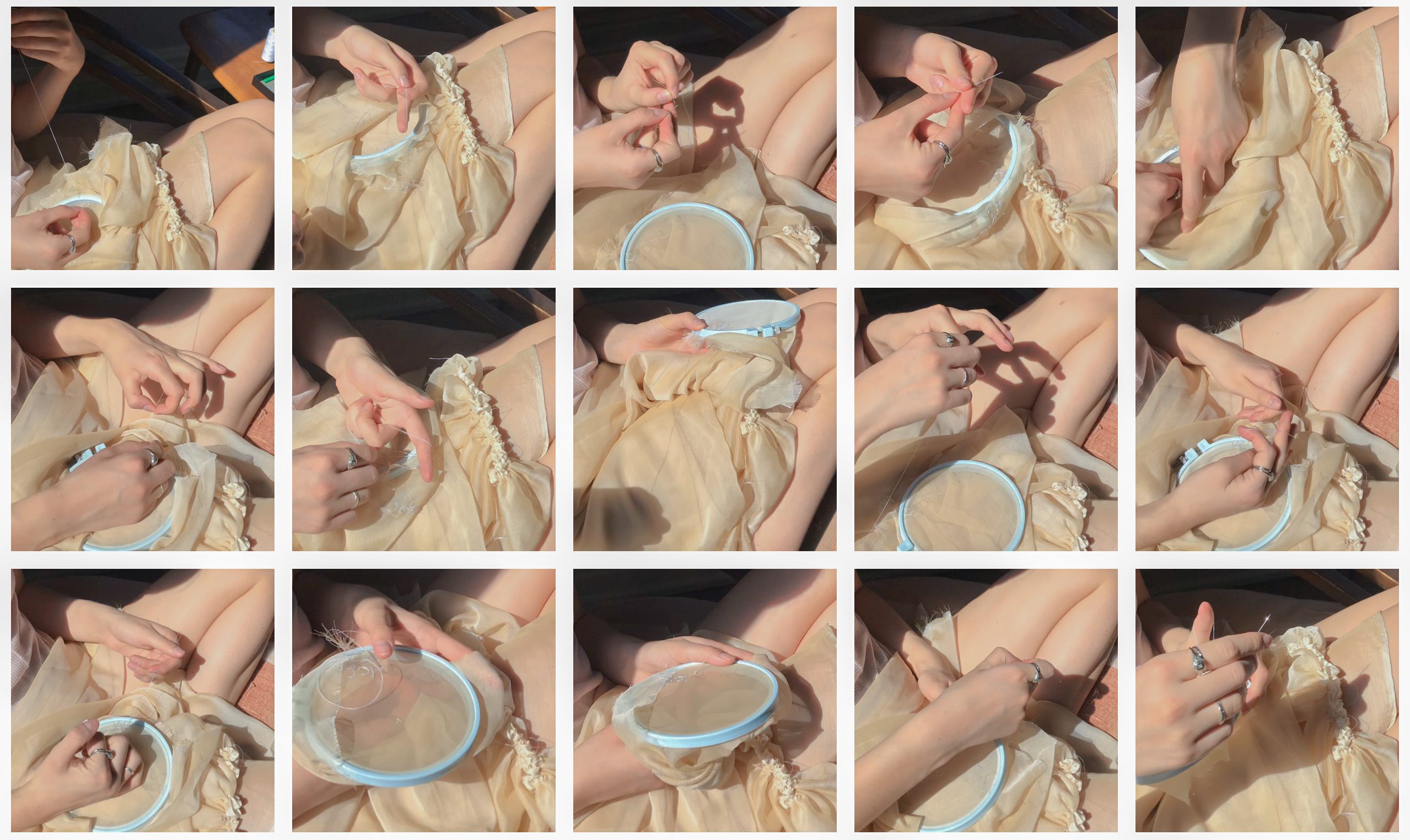

Through the framework of ecofeminism, I am considering how patriarchal structures take advantage of femininity as a tool to profit from and control women (and all people who are not heterosexual cisgender men). In looking at domesticity and the historical confinement of women to the private sphere, we see that “women’s work” constitutes invaluable yet unpaid commodities. As a traditionally domestic and feminine practice, sewing produces “feminine aesthetics;” sewing allows me to perform both domestic rituals and feminist resistance by mimicking the practices of domestic seamstresses and craftswomen such as my grandmother, and by drawing from the traditions of feminist artists who sew and embroider to resist, such as Judy Chicago.

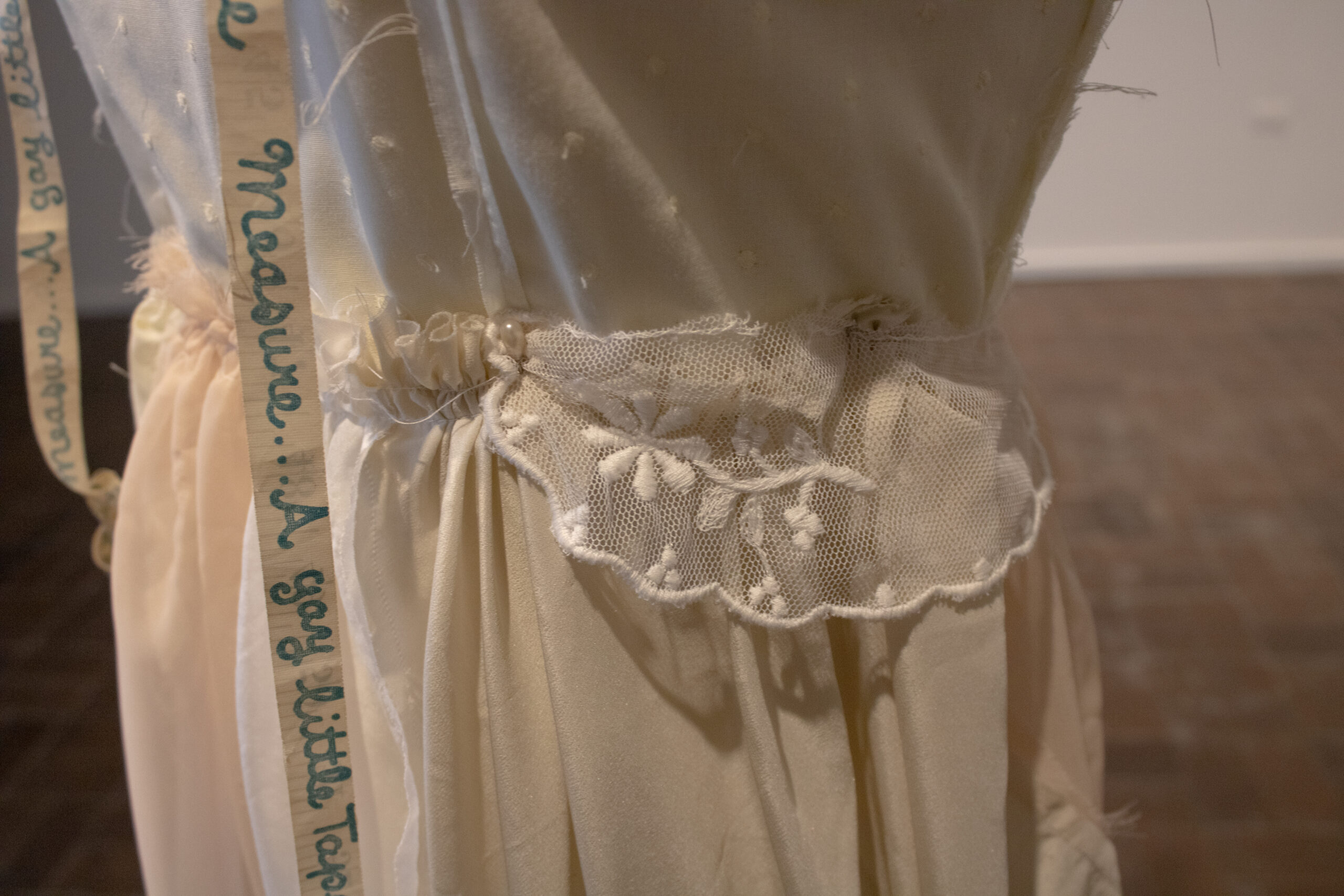

Further, types of garments, construction techniques, decorative traditions, ways of sewing, and materials themselves are grounded in histories, and present ways to connect and identify with these crucial aspects of personhood. My wedding dress and veil, for example, draw inspiration from the quilting and embroidery practices of my grandmother, which hearken to my family history, my grandmother’s expressions of femininity, and her Judaic needlework practices; the ribbon roses are directly from a sewing kit that she gifted me when I was a child. In using recycled and found materials, I intend to resist the general throwaway mentality that the fashion industry (or really any industry) relies on, and I consider the notion that each piece of material has its own history – it has come into being and has followed a certain progression of transformations in order to come into my possession.

I became interested in investigating weddings as both embodiments of oppressive power structures (patriarchy, misogyny, homophobia, materialism, exploitation), and as foundations that construct my heritage and family and serve as a way for diasporic Jews to live out our heritage in environments in which we have largely become assimilated. This dive into Judaism led me to examine the ways in which Judaism deals with gender, and how oftentimes, diaspora has necessitated a strong attachment to tradition – including gender roles – in order to maintain a semblance of culture. On the veil, I embroidered the blessing that my mother says over me each Shabbat (the traditional blessing from the mother over the daughters) and a folk song about a romance. Through this embroidery, I am renegotiating and exploring my relationship with femininity in Judaism, and working actively to maintain a cultural identity.

Ultimately, I intend to walk the very narrow path between critiquing harmful structures and inviting the nuance and ambiguity that comes with heritage, tradition, and ritual.

Works Cited

Gaard, Greta. “Toward a Queer Ecofeminism.” Hypatia: A Journal of Feminist Philosophy, vol. 12, no. 1, Jan. 1997, pp. 114–137, 10.2979/hyp.1997.12.1.114.